![]() Nyitólap

A könyv kivonta Tartalomjegyzék

Könyvismertető Édesapám

emléke, pdf

Nyitólap

A könyv kivonta Tartalomjegyzék

Könyvismertető Édesapám

emléke, pdf ![]()

|

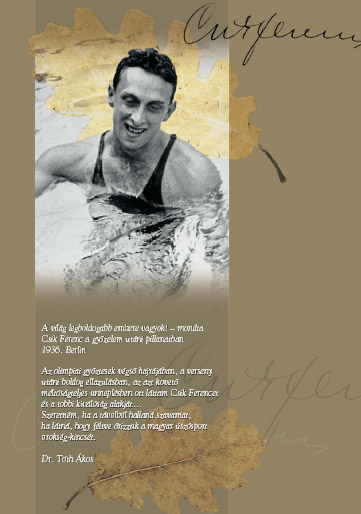

DEDICATION Go Ferkó….Go Ferkó….Push, push, push….! It’s as if there

isn’t a single day, that István Pluhár’s legendary words of encouragement during

his radio commentary in the decisive moments of the 100 meter freestyle finals

at the 1936 Olympic Games in Berlin. Watching the worn movie footage, listening

to the lone radio commentator’s anxiety and encouragement, reliving the heroic

struggle and the extraordinary victory brings tears to my eyes, time and again. Later, through lessons learned from this victory, trainers were able to develop improved conditioning methods and programs, leading to ever-greater achievements. An indispensable partner in every trainer’s route to success is his charge, the competitor, who in turn puts his faith, his talent and his perseverance into his master’s hands. Ferenc Csik happened to be an ideal subject of this champion-molding method. He can be an example for today’s competitors, and for our era’s young people in general, because he was also exceptional as an ordinary human being. |

Not only immediately following his Olympic victory, but

subsequently thereafter for years, written articles in various papers and books

mentioned his name, analyzed his persona.

Ferenc Csik would turn 90 years old this year (2003). He

could be living in good health, peacefully in retirement, and I would be happy,

if he knew, that still today he lives amongst us in our memories and we all hold

him in our highest esteem.

The achievements of Hungarian world class athletes and

Olympic champions, their lives and careers, is not only fundamental academic

course material in the physical education field, but is a proven fact. Emphasis

is placed on respecting our past, as without that, we would be floundering in

thin air, without tangible foothold, and would be incapable of creating a

meaningful future.

During the past few decades, having watched Éva Székely,

András Hargitay, Tamás Darnyi and many other world‑class swimmers, either on

film or live, in every single movement of theirs, in every single quiver of

their muscles, in their every single gasp for breath near exhaustion, I saw the

movements of all the greats who preceded them. In the Olympic victors’ closing

sprint, in their post‑race joyous relaxation, and their basking in the crowd’s

adulation immediately after the victory, still today, I see the image of Ferenc

Csik and the other outstanding athletes. Similar feelings well up within me,

whenever I hear Tamás Széchy, László Kiss and other outstanding Hungarian

trainers and coaches discussing and expressing their opinions. Hidden within

their stories, there is also testimony to the achievements of the great sporting

predecessors of the distant past, Imre Sárosi, Jenő Bakó, etc., decades of

experience of the masters.

This is the inheritance in the annals of Hungarian swimming,

which was enriched by Ferenc Csik. I wish, that he could see from the great

distance, that together with my colleagues — those within the folds of the

University of Physical Education, as well as those outside it — we jealously

guard this inherited treasure with both hands, which blossomed into such a rich

collection during the passing decades.

Ferenc Csik’s carrier was extraordinarily harmonious between its sporting and civil paths; started as club Captain, newspaper editor, served his internship at the University Clinic, teacher at the College of Physical Education, then eventually practiced as a physician, a cardiologist, and as a sports doctor.

FOREWORD

On the marble tablet in front of a pedestal mounted bust in the Keszthely cemetery, this is inscription may be read:

Dr. Ferenc Csik

assistant lecturer, school of medicine

100m freestyle olympic champion of 1936

1913-1945

“Here, you must live and die”

The letters are weather beaten, but time has no impact on the words’ meaning. Today, they are just as emotive as ever, for friends, for strangers, and especially for me…

His mother — understandably — spoke of him often and fondly, our grandmother thus lured him into our consciousness. I would have loved to know everything about my father, yet I still ran from finding the answers. As the years passed, the occasional discovery which always revealed something new — at times only a friendly gesture towards Ferenc Csik, held in high esteem by so many — started to break down this inner denial within me.

A blue school notebook was the last straw that finally compelled me to write about my father. Until now, it was resting amongst so many other pieces of paper. Hand written on its cover, it says German 1929/30. Dictionary, I thought, and until now I hadn’t even bothered to leaf through it. For some reason though, I had opened it and I was astonished, for it turned out to be his personal hand written notebook! His first entry in it was dated as January 30th, 1930, when he was still a high school student. It is as if the notebook had addressed me personally, because some years later January 30th became my birthday. Having taken this as a sign of special importance, the material resting in the drawer had repeatedly began to gnaw at me, and yet it felt as if I was threading on forbidden territory as I reached for it with a measure of trepidation. Slowly it materialized as a gift in my hands, because it was through this that I got to know my father!

Without the need to go into its entirety, through a few episodes of his private life, I wish to describe the environment which was instrumental in forming Ferenc Csik’s character, and to introduce the swimmer who until now was only known through fragments of newspaper articles, and also through this doctor’s hitherto unknown side. Since both a school and a prize for sporting achievement were named after him, I will round out the material with his deep-felt — and in the context of sports history, arguably profound — thoughts. The recollection is not merely a manifestation of present day reverence, but rather brings into focus the fact, that to this day there would be a need for his unassuming and engaging personality.

Time is all‑powerful. With its feet, the metronome tramples the present into yesterday, then into the distant past. Meanwhile, like sands of the hourglass, the unforgiving oblivion sifts ad infinitum. Only remembrance can lure the past into the present!

Csik Katalin

(He was an infinitely good person, good father, and a conscientious medical doctor, who could always cope with any situation. During the 32 years fate had allotted to him, he accomplished as much as others could only hope to accomplish in a long-long lifetime. How was he able to find time to do all that? That is something that should be taught…) His Farewell Letter ( October 6, 1944):

My dear and only Sweetheart,

Now, that I had received my conscription papers and more than likely I will have to report for military duty — without the least bit of pessimism or feelings of faint of heart —, I sit down to write to you, just in case something should happen. You know of course, that I always viewed my fate with a certain optimistic fanaticism, and now too I look forward to the future with tranquility, and with hopes, but without a doubt, we are living in troubled times, and we must be prepared for any eventuality. Knowing you, I don’t want to unnecessarily alarm you, and that’s why I leave for posterity what I would like to express in a farewell, in case I would not be granted that opportunity.

Whatever material possessions, movables I may leave behind, naturally you are free to dispose with as you choose, but of course these are not some immense treasures, and apart from the medical equipment (X-ray, microscope) which you best sell at the earliest, it would be good to if you would hold on to them, as long as my mother or your parents, as the case may be, are able to help you out. The two little children, Ferke and Kati, on whom you can base your future, represent a much greater treasure. I know that they mean a great burden, and will place a great load on your frail shoulders, but parental love will make you stronger, and my mother and your kind parents will support you, and I will be beside you too, just as our father was with us, even in death.

Always, especially in times of difficulty, think of how these sweet little munchkins — our possessions — grow, develop just the way you bring them up by putting your heart and soul into it, with love and with hard work. I know that they will not be suffering a lack of love, and if fatherly sternness is required, you will provide that too, and I only want to ask one thing of you, regardless what problems you may have, don’t be agitated and don’t ever let them feel that it’s a burden for you. I just want to set my mother as the example for you, that we can struggle to overcome any obstacle, if we have the will — the ability to grind away for achieving a set goal.

My dear Sweetheart! Regardless how much I would love to live, to be with you and to enjoy the warmth, love, which I received from you and the family, still I calmly resign myself to the possibility of passing away too. The knowledge reassures me that here too I am doing my duty, and I’m certain that if it all turns out for the better, I will return.

In parting, I thank you for everything-everything. I know that it’s easier for the one departed, on the other hand you should find solace in our Ferke and Kati, whom along with you and my mother, and together with the entire family, I leave behind with a heavy heart.

Kissing you ever so many times from beyond the grave too, your loving

Ferkó

The Athlete

In 1931 Budapest, he joined the BEAC Sports Club as a medical student.

In the 1932 Collegiate Championship he was victorious in the 100-meter sprint, and afterwards he won every single event he entered. Throughout the following six years, right up until he retired, he kept his number one ranking.

In a swim meat organized in Turin in 1933, he merited the silver medal in the 100m free style, placed third in the 50m free style and was a member of the victorious 4x200 meter free-style relay team, and here is where he first swam under 1 minute. He was victorious in the Hungarian championship’s 100m free style event.

As Hungarian champion of the 100m free style event, he launched into a hard and conscientious routine to prepare for the 1936 Berlin Olympic Games.

In a subsequent newspaper article of his, Pál Peterdi reflected on how exactly the trainer evaluated Ferenc Csik:

Any time I quizzed József Vértesy about him, his words turned much more passionate than usual: “Ferkó…. Ferkó, ah, Ferkó….— that’s all he said every time, meanwhile his arms gesturing with broad arm swings, with upward swelling movements. Saying that Ferkó was the ultimate pupil, the perfect competitor, the purest human being…ah! — there was a dreadful necrology in that gesture.

One time, he produced a black elastic band from his briefcase. That too was once Ferkó’s, with which he used to tie his feet together, whenever he wanted to swim using his arms only. Vértesy had it with him for over twenty years, waiting for anyone worthy of Ferkó’s elastic band.

His Master immensely valued his attitude towards training and towards his fellow human beings. During his entire competitive career he participated in every event as a BEAC member.

This list of his victories is compiled from the 1940-1941 editions of Képes Sport (Sports Illustrated):

- Winner of two gold medals in the 1934 European

championships held in Magdeburg. Member of the 4x200 meter free-style

relay team (Maróthy, Gróf, Lengyel, Csik)

- Winner of the 1934 “Grand Prix” held in Paris. In

recognition of his victory, from the French hosts he received a giant

cobalt blue Sevre vase and a blue-red silk ribbon with a sterling silver

tassel bearing the inscription “Grand Prix de Paris, 1934”.

- Started in 55 races in 1934; 39 times in the 100

meter free-style.

- Won three gold medals in the 1935 World

Intercollegiate Championship games, became 100 m World Intercollegiate

Champion with a then world record time of 59,4 seconds.

- Olympic Champion in the 100 meter free‑style event

and member of the 4x200 meter free-style relay team which won the bronze

medal at the 1936 Berlin Olympic games at the pinnacle of his career.

- 100 meter free-style Champion of Hungary, and was a

member of the National Championship winning 4x200 meter relay BEAC team

(Dienes, Lengyel, Kiss, Csik) in 1937. Won four gold medals in the World

Intercollegiate Championship: the 100 meter free-style, the 200 meter

breaststroke, and as member of the victorious relay team winning the

4x200 meter free-style and 3x100 meter medley events.

- 100 meter free-style Hungarian Champion in 1938.

The Pesti Hirlap’s (Budapest Chronicle) 1938 yearbook published the

following statement: it is virtually impossible to list all of Ferenc

Csik’s victories; he participated in invitational competition events

from Africa to Stockholm, practically everywhere.

- In the 1939 his achieved his most significant

victory at the traditional Grand Prix of Paris, where he won the 100

meter free-style with a time of 59,9 seconds after which the French

president Lebrun personally handed him the trophy, a gigantic cup.

- Summary of his achievements:

The radio reporter presented the unforgettable atmosphere of the race in the following style (Berlin, 1936):

István Pluhár: Swimming

In the Olympic stadium the murmur and enthusiasm of the more than a hundred thousand spectators accompany the last few athletics events as they are winding down, the relays, the start of the Marathon. Crowds lined the more than 42 km long route of the Marathon. Over the immense area of the stadium-town and over its wide roads, loudspeakers broadcast the turn of events as they unfolded, and the news and results spread by word of mouth. Beside the basketball courts in the tennis stadium the crowds were screaming, and wrestlers were panting in the heat on the mats of the Deutschlandhalle.

Hungarian hearts were throbbing around the swimming pool. As the roar from the Olympic stadium drifted over around three o’clock, so the crowd’s almighty clamor had echoed in response. In the twenty thousand seats a few extra hundreds were crowded in.

The brass played snappy marches. The musicians’ white uniforms had lent the event an even livelier atmosphere, and near the diving tower’s base, on a little bench, a group of competitors arm-in-arm were moving and swaying with rhythm of the tunes.

— Lenkey! Lenkey! — could be heard from here and from there.

Magda Lenkey, the Hungarian women’s swimmer, flashing her customary smile, with a slightly forced composure she peeled off her sweat suit, while with a languid wave of her arm she responded to the cheers. The Hungarian girl was a popular member of the international swimming community, and this was the reason why the crowd called out her name with various accents.

The women swimmers lined up on the starting blocks for the first round of the preliminaries of the women’s 100 m freestyle event. In the stadium, the clock’s hands on the skyward thrusting rectangular tower showed exactly three o’clock.

Then suddenly the eight bodies hit the water, and in a minute and a half we knew that the Hungarian colours had not managed to get into the deciding final heat.

One more women’s preliminary heat is left to play out. The fleeting time moves on leaden feet. We keep glancing at our watches a hundred times, if once.

It’s still not 15:20.

How many times we had discussed fate’s wickedness, for it had relegated Csik to lane number seven! While in the water, he could not even hope to see the two Japanese, who swam excellent times in this crystal clear sparkling water. And right beside him is the third Japanese, who with clever tactics could distract his attention to slow him down…

— Hungarian fate — moans someone, always fall into the worst circumstance.

— Hungarian fate — says someone else, for Hungarians always have to work twice as hard as someone else, if they want to succeed.

At last a group in the crowd breaks into thunderous applause. No more time for theories, not more time for wondering.

— Csik! Csik! Csik! — is heard all around.

One of the spectators attempts to be enthused.

— Huj, huj, hajrá! Huj, huj, hajrá! (Hip, hip , hurray!)

But are the voices sounding strange?! As if they were struggling. As if the sounds had a hard time to billow out.

Csik glances towards them. He looks as pale as the moon’s face. One can almost feel that his lips are cold. Perhaps he is trembling too. His smile is weary, he hardly shows any sign of life. Taguchi dives into the pool beside him, swims a few meters, and climbs out at the starting block. Fick is sitting on the number four starting block. His massive chest heaving like bellows, as if he wants to inhale all the air in the stadium.

Csik is flailing with his arms. His masseur is at his side, rubbing his legs and arms. The two Japanese over on the far side of the pool, are standing motionless and qualm. Like two eastern statues. Their tiny eyes under jet black hair looking at some faraway land’s wonderment.

Gädeke, the German starter, mounts the table behind the swimmers. The seven swimmers kept one eye on him all along, for they peeled off their sweat suits in unison. Gadeke is just as pale as the seven swimmers. Keeps looking at his starting gun, keeps glancing left and right. A soft whistle blow rings out, Dr. Donath’s raised right arm indicates that the race is about to start. Gädeke acknowledges the sign with a slight bowing of the head, and in a low voice calls out:

— Auf die Platze! (On your marks)

The seven swimmers step up on to the seven starting blocks and take up their starting positions, but with one eye they furtively scan the Starter behind them. The spectators are deathly quiet, only up at the top, in front of the microphones do the twenty reporters talk nonstop.

A curt command is called out, the starting gun crackles, and the world’s seven fastest swimmers hit the glimmering water.

It is just one moment, even though it looks like an eternity, until the seven pairs of arms swirl like so many windmill vanes leaving a wake in the waves. And at long last after this moment, we see that Csik’s lanky frame is in front as a result of his fantastic start, and the Hungarian is in the lead. A collective scream breaks out in the stadium. But all is unintelligible. This is a real pandemonium, as if some unchained feelings would have broken absolutely free.

The water is churning, and the pool is sluing with tremendous waves. On the far side, a jet-black head bores forward at an unbelievable rate. By the midway mark it is already level with Csik’s head…already passing him… and the other Japanese head is surely pulling even with him too…

— Csik!...Csiiik!...Csiiiiiik!.... — Now the Hungarian camp erupts with a scream. Now is when all their passion breaks loose, which would love to drive, help, encourage, and strengthen the young Hungarian. The shrill sound of the “i” (sounding like “ee”) in their screams, a whole nation’s fragile hope is riding on him, when Yusa’s hand touches the pool and turns with infernal momentum.

Time flies, the seven swimmers fly. The Hungarian screams die down.

— Everything is in vain — says the defeatist.

And now at the pool’s midway mark, past the first seventy-five meters, the Hungarian arms’ strength increases, Hungarian hearts’ fervour burns ever more passionately, and now confident of victory, every stroke becomes more powerful.

Is the Japanese flagging? No, Csik is increasing his tempo.

— Csik!...Csiiik!...Csiiiiiik!…

A blurred, terrible cacophony follows the seven swimmers’ last twenty meters. The German, the American screams blend into Hungarian calls, and when in the final ten meters the seven swimmers enter the do-or-die final phase of their contest, and it’s as if only Csik’s name is on every spectator’s lips. The German Fischer, the two Americans no longer count in the outcome of the race, the Hungarian alone is battling the three Japanese.

Feri!...Go Feri! Push, push, push … Only a few more strokes to go!

It wasn’t even our mouths shouting, but rather our hearts. The throng is swirling, buzzing and clamoring all around, as the feverish excitement in our minds, and the torment of agony in waiting for victory is squirming in our hearts. Then suddenly there is the final, thundering whoop of excitement. Csik’s hand strikes the pool’s end wall. But the Japanese hand touches it too.

Now all is quiet. All eyes dart confusedly all over the place, every gaze furtively searches for a promising “yes”, or some reassuring word. The Hungarians, Deutsch, Polish, Germans, Americans, Austrians, Swedes and Swiss all look at each other, but no one dares to utter the word, that Csik had won. Members of the race committee huddle with the timekeepers. Their quivering hands grip the stopwatches, and are very animated, whispering.

There is Csik gripping the steel railing. He runs his fingers through his hair. Throws his head back and submerges momentarily, then some distorted exhaustion indicating excitement twitches on his lips …

Nicolaus Horthy Jnr, suddenly leaves the race officials, and rushes over to congratulate Csik, bends down and plants a kiss on his face. István Bárány also rushes to his side, just about falls into the pool, as he plants a kiss on the Hungarian swimmer’s face. Fischer swims over to his great rival to congratuplate him with a hug.

The Hungarian camp let loose with screams of joy.

— He won! He won! He is first! Csik is the winner!

Dr. Kornél Kelemen, jumps over the railing out of the boxes, and runs over to the poolside. Nicolaus Horthy Jnr. pulls the winner out of the water, then in the clutches of a thousand arms, and the Hungarian sports officials’ hugs dry the water off him.

The photographers commence a photo barrage of the Hungarian spectators, who in turn keep up their vociferous encouragement:

— Huj, huj, hajrá! Huj. Huj, hajrá! (Hip, hip, hurray! Hip, hip, hurray!)

The Hungarian shouts fill the stadium. Every mouth is screaming the encouragement, and the hugs, which was initiated by the Hungarian officials, the entire stadium is mimicking them in earnest.

All of Europe, indeed the entire world is jubilant at the Hungarian win, because Hungary had sent one of the greatest heroes, the winner of one of the most classical of events to the Berlin Olympics, after all it is the Hungarian nation that placed him by the pool.

Csik’s victory had elicited recognition from all nations of the globe, and this recognition hailed the Hungarian flag ascending the mast of victory.

*

Ferenc Csik’s victory meant that succeeding Alfréd Hajós and Zoltán Halmay, a Hungarian is again the world’s fastest swimmer. Those results though, which our youth have achieved in other categories, bear witness to the fact that Hungary’s swimmers hold a leading position in Europe. The men’s 4x200 meter relay team bowed only to the USA and Japanese teams, but had concurred every other relay team and thus gaining third:

Csik won in his best ever time of 57,6 sec. The second place Japanese, Yusa, swam 57,9 sec, with which he was clearly relegated to the background.

Csik’s time of 57,6 sec was also a record when compared to times achieved in previous Olympics. He bettered the time set by the then current world’s most famous swimmer, the twice Olympic champion Johnny Weissmüller’s 58,6 sec, as well as the time of 58,2 sec. set by Yasui Miyazaki at the 1932 Olympic Games 100-m freestyle event.

Csik the sporting individual – medical student – the humble and affable swimming champion, who was loved by everyone, was a role model for all of us, and he remains that for the benefit of all future generations.

Even in the opinion of well informed experts, the present era’s

ideal is one

who leads a life with both body and mind in harmony,

and perhaps I’m not exaggerating,

if I simply state that even amongst those

the ideal is the athlete.

Ferenc Csik

Minden jog fenntartva © 2003 Csik Katalin

közreadja

Csik Katalin, a könyv szerzője

A megjelent könyv címe: „ A test és lélek harmóniájában, Csik Ferenc emlékezete”.